Technical Volume 1:

Cybersecurity Practices

for Small Healthcare

Organizations

2023 Edition

iTechnical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Table of Contents

Introduction 1

Where Can You Go for Addional Resources? ........................................................................................................................................2

What are Managed IT Services? ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3

Different Types of Managed IT Services ................................................................................................................................................... 3

How Do I Select a Vendor? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4

Document Guide: Cybersecurity Practices 7

Cybersecurity Practice #1: Email Protection Systems 9

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................... 9

1.S.A: Email System Conguration................................................................................................................................................................ 9

1.S.B: Education

......................................................................................................................................................................................................10

1.S.C: Phishing Simulations .............................................................................................................................................................................11

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 12

Cybersecurity Practice #2: Endpoint Protection Systems 13

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................13

2.S.A: Basic Endpoint Protection Controls ...........................................................................................................................................13

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 15

Cybersecurity Practice #3: Access Management 16

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................16

3.S.A: Basic Access Management ................................................................................................................................................................16

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 18

Cybersecurity Practice #4: Data Protection and Loss Prevention 19

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................19

4.S.A: Policies ............................................................................................................................................................................................................19

4.S.B: Procedures ...................................................................................................................................................................................................20

4.S.C: Education ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 21

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 21

Cybersecurity Practice #5: Asset Management 22

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................22

5.S.A: Inventory .......................................................................................................................................................................................................22

5.S.B: Procurement ...............................................................................................................................................................................................23

5.S.C: Decommissioning ................................................................................................................................................................................... 23

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 23

Cybersecurity Practice #6: Network Management 24

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................24

6.S.A: Network Segmentation .......................................................................................................................................................................24

6.S.B: Physical Security and Guest Access ............................................................................................................................................25

6.S.C: Intrusion Prevention .............................................................................................................................................................................25

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 25

iiTechnical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Practice #7: Vulnerability Management 26

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................26

7.S.A: Vulnerability Management ............................................................................................................................................................... 26

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 26

Cybersecurity Practice #8: Incident Response 27

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................27

8.S.A: Incident Response ..................................................................................................................................................................................27

8.S.B: Information Sharing ...............................................................................................................................................................................29

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 29

Cybersecurity Practice #9: Network Connected Medical Devices 30

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................30

9.S.A: Medical Device Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 30

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 30

Cybersecurity Practice #10: Cybersecurity Oversight and Governance 31

Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons .......................................................................................................................................................31

10.S.A: Policies.........................................................................................................................................................................................................31

10.S.B: Cybersecurity Risk Assessment and Management

33.......................................................................................................

10.S.C: Security Awareness and Training .............................................................................................................................................. 35

10.S.D: Cyber Insurance ...................................................................................................................................................................................35

Key Migated Threats ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 36

Appendix A: Acronyms and Abbreviations 37

Appendix B: References 39

Tables

Table 1. Five Prevailing Cybersecurity Threats to Healthcare Organizaons 7...................................................................

Table 2. Cybersecurity Pracces and Sub-Pracces for Small Organizaons 7...................................................................

Table 3. Phishing Detecon ...............................................................................................................................................................................11

Table 4. Eecve Security Controls to Protect Organizaon Endpoints ...........................................................................13

Table 5. Security Controls Enabling Organizaons to Manage User Access to Data ................................................ 16

Table 6. Example Data Classicaon Structure ...................................................................................................................................20

Table 7. Roles and Responsibilies of an Incident Response Team 28.......................................................................................

Table 8. Eecve Policies to Migate the Risk of Cyber-Aacks 32...........................................................................................

Table 9. Acronyms and Abbreviaons .........................................................................................................................................................37

1Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Introducon

Healthcare providers are being attacked by malicious actors, some from inside their own organizations

and others from around the globe. While news reports may insinuate larger providers are targeted

more frequently, the data suggests smaller ambulatory practices are also targeted and can suffer greater

proportional damages. The rationale is that smaller providers are generally less prepared to detect,

respond, and recover from cyber-attacks.

Indeed, the ve threats identied in the Main Document can be very disruptive to small organizations. For

example, if a small provider practice loses a laptop with unencrypted Protected Health Information (PHI),

a publicized breach could result in consequences for the provider’s patients and the practice’s reputation.

Technical Volume 1 outlines healthcare cybersecurity best practices for small healthcare organizations.

For this volume, small organizations generally do not have dedicated information technology (IT) and

security staff dedicated to implementing cybersecurity practices. Consequently, personnel may have

limited awareness of the severity of cyber threats to patients and to your organization, and thus, not

recognize the importance of cybersecurity and how to address it.

Many small healthcare organizations provide direct healthcare services to their patients in ambulatory

environments. These environments have less overhead and, because of this, are often more cost-

effective than large acute facilities. Cost-effectiveness enables small healthcare organizations to sustain

operations, maintain nancial viability, justify future investments (e.g., grants) and, in the case of for-

prot organizations, generate an acceptable prot. Conducting day-to-day business usually involves the

electronic sharing of clinical and nancial information. This is done internally within the small healthcare

organization and its physicians and externally with patients, providers, and vendors that have a role

in managing your organization and maintaining business operations. For example, small healthcare

organizations transmit nancial information to submit invoices and insurance claims paid by Medicare,

Medicaid, Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs), and commercial insurance companies.

In general, small organizations perform the following functions:

• Clinical care, which includes but is not limited to sharing information for clinical care, transitioning

care (both social and clinical), electronic prescribing or “e-prescribing,” communicating with

patients through direct secure messaging, services provided through telehealth, and operating

diagnostic equipment connected to a computer network (e.g., ultrasound and picture archiving and

communication systems (PACS)).

• Provider practice management, which includes patient access and registration, patient accounting,

patient scheduling systems, claims management, and bill processing.

• Business operations, which include accounts payable, supply chain, human resources, IT, staff

education, protecting patient information, and business continuity/disaster recovery.

If you would like to conrm your status as a small healthcare organization, refer to the HICP Main

Document, Table 1.

Just as healthcare professionals must wash their hands before caring for patients, healthcare

organizations must practice good cyber hygiene by including cybersecurity as an everyday, universal

precaution. Like hand washing, cyber awareness does not have to be complicated or expensive. In fact,

simple cybersecurity practices, such as always logging off a computer when nished working, are very

effective at protecting sensitive information.

Introduction

2Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

This volume takes into consideration regulations, guidance, and best practice recommendations made

by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and its operating divisions and staff divisions.

Operating divisions and staff divisions include, but are not limited to, the Ofce for Civil Rights (OCR),

the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response

(ASPR), the Ofce of the Chief Information Ofcer (OCIO), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS), and the Ofce of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC).

Other recommendations are derived from guidelines and leading practices from the National Institute of

Standards and Technology (NIST), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Cybersecurity

and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

Many small healthcare organizations use third-party IT support and cloud service providers to maintain

operations that leverage current technologies. Given the complicated nature of IT and cybersecurity,

these third-party IT organizations can be helpful in identifying, assessing, and implementing cybersecurity

practices. Your IT support providers should be capable of reviewing the practices in this publication to

determine which are most applicable to your organization.

In addition to IT requirements, small healthcare organizations must comply with multiple legal and

regulatory standards as well as contractual agreements. Healthcare practices often ensure compliance

by creating an internal infrastructure of personnel and procedures governing how they safeguard the

maintenance and transmission of sensitive data. Organizations may be subject to directives from:

• Information blocking and interoperability regulations for patient information mandated by the ONC

Cures Act Final Rule.

• Medicare Access and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Reauthorization Act of 2015

(MACRA)/Meaningful Use.

• Privacy and Security Rules of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)/

Health Information Technology Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH).

• Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS).

• Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) regulations for the

condentiality of substance abuse disorder treatment records (42 CFR Part 2).

• Changes to the Stark Law physician self-referral regulations and the related anti-kickback safe

harbor took effect in 2021, allowing for the donation of cybersecurity technology and necessary

services used predominantly to implement, maintain, and reestablish effective cybersecurity.

• State law requirements for maintaining patient treatment records, as well as the safeguarding and

destruction of data containing health information.

Where Can You Go for Additional Resources?

The 405(d) Program and Task Group is a collaborative effort between industry and the federal

government, which aims to raise awareness, provide vetted cybersecurity practices, and move

organizations towards consistency in mitigating the current most pertinent cybersecurity threats to the

sector. Please explore the 405(d) website to learn more about all products and resources available to

our stakeholders.

CISA has published the CISA Services Catalog, which is intended to serve as a single touch point

for anyone interested in CISA’s services. An interactive section of this resource allows health care

organizations to quickly focus on the services that best t their capabilities and challenges, based on

Introduction

3Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

their characteristics and maturity level. For example, healthcare providers can select services they’re

interested in across four categories—cybersecurity, risk management, infrastructure, and emergency

communications—then choose their readiness level. After these selections, they are then presented with

all the CISA services most appropriate for them. Also in the resource, users can access and peruse all CISA

service indices and understand how CISA’s staff is organized and distributed throughout the country.

For additional resources please visit 405(d), OCR, HC3, NIST, and FBI.

Types of Managed Services in Health IT

The scope and breadth of information technology in healthcare has evolved rapidly in the twenty-rst

century. Health-IT is a critical component of almost every healthcare organization. Electronic health

records (EHRs), medical devices, and business management software applications have been integrated

into clinical practice and health care operations.

However, for various reasons, not all healthcare organizations have the resources to build out a team

of experts to operate or maintain their information technology assets. This is especially true for small

healthcare organizations. To meet EHR use, health information exchange, and other IT requirements,

many healthcare organizations depend on managed IT services from an outside vendor.

What are Managed IT Services?

Managed IT services (outsourced IT) is a third-party service that provides infrastructure, IT, and other

technical support to healthcare organizations. These service providers are often referred to as a managed

service provider (MSP). To simplify our discussion, we will label all outsourced IT services of any size or

scope as being provided by an MSP vendor.

MSP service offerings vary widely, covering everything from cybersecurity needs, voice-over-internet-

protocol (VoIP), telehealth solutions, backup recovery, and integrated business activities. Healthcare

organizations often seek out MSP support because they cannot hire and manage an internal IT team, or

they prefer the expertise and exibility of contracted services.

As MSPs cover a broad range of many different types of managed services, it is important to understand

what each vendor includes when you are contracting services. Knowing what the service options are and

which ones your healthcare organization needs is an important rst step.

Different Types of Managed IT Services

There are various types of vendors and services available to healthcare organizations. Not all providers

will offer the same types of IT services. One MSP might be a small, locally based IT contractor that

provides a handful of services; or specializes in just one type of service. Other MSPs may seek to offer

a comprehensive selection of IT and security services to be the sole vendor for an organization’s IT

management needs. Regardless, if your healthcare organization wants to outsource its IT management, it

is good to know what services are offered and what services are included in your contract.

• Managed Networks and Infrastructure: With this type of service, an MSP generally takes on the

entirety of network tasks. This includes establishing internet connectivity, managing local wired

networks, and wireless networks plus various connections for your healthcare organization. They

may also manage data backup, recovery, and storage options.

Introduction

4Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

• Managed Security: A managed security service provider (MSSP) provides outsourced monitoring and

management of security devices and systems. Common services include managed rewall, intrusion

detection, virtual private network (VPN), vulnerability scanning, and malware prevention/anti-virus

tools. MSSPs will often conduct cybersecurity risk assessments, which is critically important for

HIPAA compliance. Some MSSPs provide consulting services for mitigating gaps identied through

the risk assessment.

• Managed Support and Help Desk Services: Typically provides all services related to IT help—

troubleshooting, resetting passwords, and dealing with advanced issues.

• Managed Print Services: With this type of managed service, an MSP will remotely assist with

document management, data and le infrastructure of multi-function devices, printers, and fax

machines. These services are most often used by organizations producing, receiving, and storing high

volumes of digital or printed documents.

• Managed Cloud Infrastructure: Cloud infrastructure management handles computing, storage,

network, and IT. Some vendors may also offer virtualization services for apps, software, operating

systems, or electronic health record systems.

• Managed Software as a Service (SaaS): With this type of service, vendors offer a software platform,

typically subscription-based, for healthcare organizations. A few examples include Microsoft 365,

Zoom, e-prescribing software, and anti-malware/anti-virus software.

• Managed Wireless and Mobile Computing: A vendor offering managed wireless and mobile computing

will implement wireless local-area network (WLAN) connections. Examples of wireless and mobile

computing are Wi-Fi networks internal to a healthcare facility, telehealth systems, and internet-of-

things (IoT) devices.

• Managed Communication Services: This type of service offers a range of communication infrastructure

like messaging software, VoIP telephone, data, and video. Examples are Ring, Zoom, and Skype.

• Data Analytics: Healthcare data analytics is the process of analyzing current and historical industry

data to predict trends, improve outreach, and better manage the spread of disease. It can reveal

paths to improvement in patient care quality, clinical data, diagnosis, and business management.

• Managed Electronic Health Record (EHR) and Practice Management: This type of service will manage

components of the main EHR and/or practice management suite. It could include ensuring the

maintenance of the EHR itself, updating workows, managing revenue cycle and billing, or other

clinical practice management needs.

How Do I Select a Vendor?

Vendor Assessment: Beginning Vendor Selection

A vendor assessment is the process of collecting information on several vendors and narrowing the

vendor eld before selecting an MSP. The challenge of narrowing a large eld of available options to a

manageable number of vendors can be daunting, but it is a critical step in outsourcing your IT.

Suggestions for Conducting an MSP Vendor Assessment

Follow the steps below to ensure your healthcare organization can conduct a vendor assessment

effectively and efciently.

Introduction

5Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

1. Assess Your IT Management Needs: Identify high priority needs and IT features that may meet those

needs. Make sure you identify what information network features you will need to achieve the goals

your organization requires for its information systems.

2. Set Information Technology Network Goals: Follow the “SMART” goals process. Goals should be

specic, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time bound.

3. Make Key Decisions: Make a list of potential deal-breakers and decide whether you want your

healthcare organization’s data to reside in-ofce, a vendor server, or in web-based storage (“cloud

storage”). To help form a list of potential deal-breakers, research vendor websites and speak to

colleagues. Making key decisions up-front will enable your practice to effectively narrow the eld.

4. Narrow the Field: You can start with vendor reviews and ratings for IT managed service providers

gathered from healthcare industry leaders. Leading reviews are aggregated and reported by

Gartner

1

and KLAS Research.

2

¡ Ask colleagues about their IT managed service provider experiences.

¡ Find information about different vendors online.

5. Design and Issue a Request for Information (RFI): Develop an RFI to solicit information from vendors

about their products and services. Ask for information about the vendor’s organizational prole,

implementation and training model, ongoing support, estimated total cost of ownership, and

availability for demonstrations. Be sure to include specic questions requesting documentation on

the vendor’s cybersecurity program including how they prepare for, mitigate against, and respond to

cybersecurity attacks.

3

Make it a requirement that any prospective MSP vendor set up ofine, off-

site, encrypted backups of information essential to your business.

4

6. Compare Vendors: Compare and evaluate RFIs returned by vendors. Rate the capabilities and the

vendor pricing to compare the costs of different MSPs. Using these comparisons will help you

narrow the eld further before conducting demonstrations.

7. Contact References and Schedule Site Visits: Ask vendors for lists of healthcare organizations who have

successfully implemented their managed service products. Contact the references and schedule

time to meet. Prepare a list of questions to gather lessons learned by the healthcare organization

before, during, and after implementation.

8. HIPAA Privacy Rule Requirements for Business Associate Agreements:

5

Business Associate Agreements

(BAAs) are a necessary tool for ensuring HIPAA Privacy Rule compliance. The negotiated terms of

BAAs are more important when a vendor will create or maintain patient information or the electronic

information systems that handle this data. Covered entities, such as physician practices and

healthcare facilities, are required to enter a BAA when they hire a third-party contractor to perform

a service on behalf of the covered entity (if the contractor will require the use of and/or access to the

1 “Gartner Peer Insights: Reviews Organized by Markets.” Gartner LLC. https://www.gartner.com/reviews/markets.

2 KLAS Research. https://klasresearch.com/.

3 “Cybersecurity for Small Business: Vendor Security.” Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/

business-center/small-businesses/cybersecurity/vendor-security.

4 Fair, Lesley. “Ransomware Risk: 2 Preventive Steps for Your Small Business.” Federal Trade Commission. November 5,

2021. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2021/11/ransomware-risk-2-preventive-steps-your-

small-business.

5 “Business Associates.” HHS Ofce for Civil Rights. May 24, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/

privacy/guidance/business-associates/index.html.

Introduction

6Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

covered entity’s PHI to perform such service). Examples of potential third-party contractors include

outsourced IT management companies, EHR vendors, and cloud data storage services.

The Final Decision

After establishing managed IT service objectives and conducting a vendor assessment, select a vendor and

enter the contracting phase. For more information on vendor contracting, see What Are Important Items

to Include in a Vendor Contract? published by ONC for Health IT.

6

Managing Vendors to Protect Cybersecurity

The threat of a cybersecurity incident compromising patient data and causing disruption to treatment

activity still exists when outsourcing some/all the IT network management to an MSP vendor. As such,

small healthcare organizations should develop and implement a plan to manage and monitor an MSP

vendor’s cybersecurity risk. For example, vendors that host patient information or interface with medical

devices warrant more thorough monitoring cybersecurity practices compared to IT vendors who only

access the information system while performing services onsite.

Monitoring intensity should be based on the level of risk presented to the healthcare organization.

Monitoring can include requesting and reviewing security-related documentation from MSP vendors

such as cybersecurity policies, proof of training, proof of conducting background investigations on their

workforce members, third-party security evaluations, and risk assessments. If the vendor is hosting data

or systems, the documentation requested may be more specic (e.g., proof of backups, actual contingency

test reports, proof of terminations and destruction certicates). For an organization to remain informed

on its security posture, an Executive Business Review (EBR) on a periodic cycle (quarterly/bi-annually) can

be requested.

Monitoring to ensure vendors are compliant with industry best practices is especially signicant to avoid a

cybersecurity attack.

Finally, management of an MSP vendor’s activities does not cease on the termination date specied in

the service agreement or contract. Requirements detailing the disposition of both access and retention

of data should be included in the service agreement. The contract should also specify how to eliminate

and document all access to patient information, as well as instructions for returning or destroying all

patient information in MSP possession. This documentation is crucial should a breach occur involving

a healthcare organization’s information after that entity has terminated its relationship with the

MSP vendor.

As mentioned previously, the practices and recommendations in this volume are tailored to small

organizations. In some cases, small organizations could also benet from selected practices in Technical

Volume 2 of this publication, which focuses on medium and large organizations. However, size is not a

determinant of who might benet from the cybersecurity practices found in each volume.

6 “What Are Important Items to Include in a Vendor Contract?” Ofce of the National Coordinator for Health IT.

October 22, 2019. https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-are-important-items-include-vendor-contract.

7Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

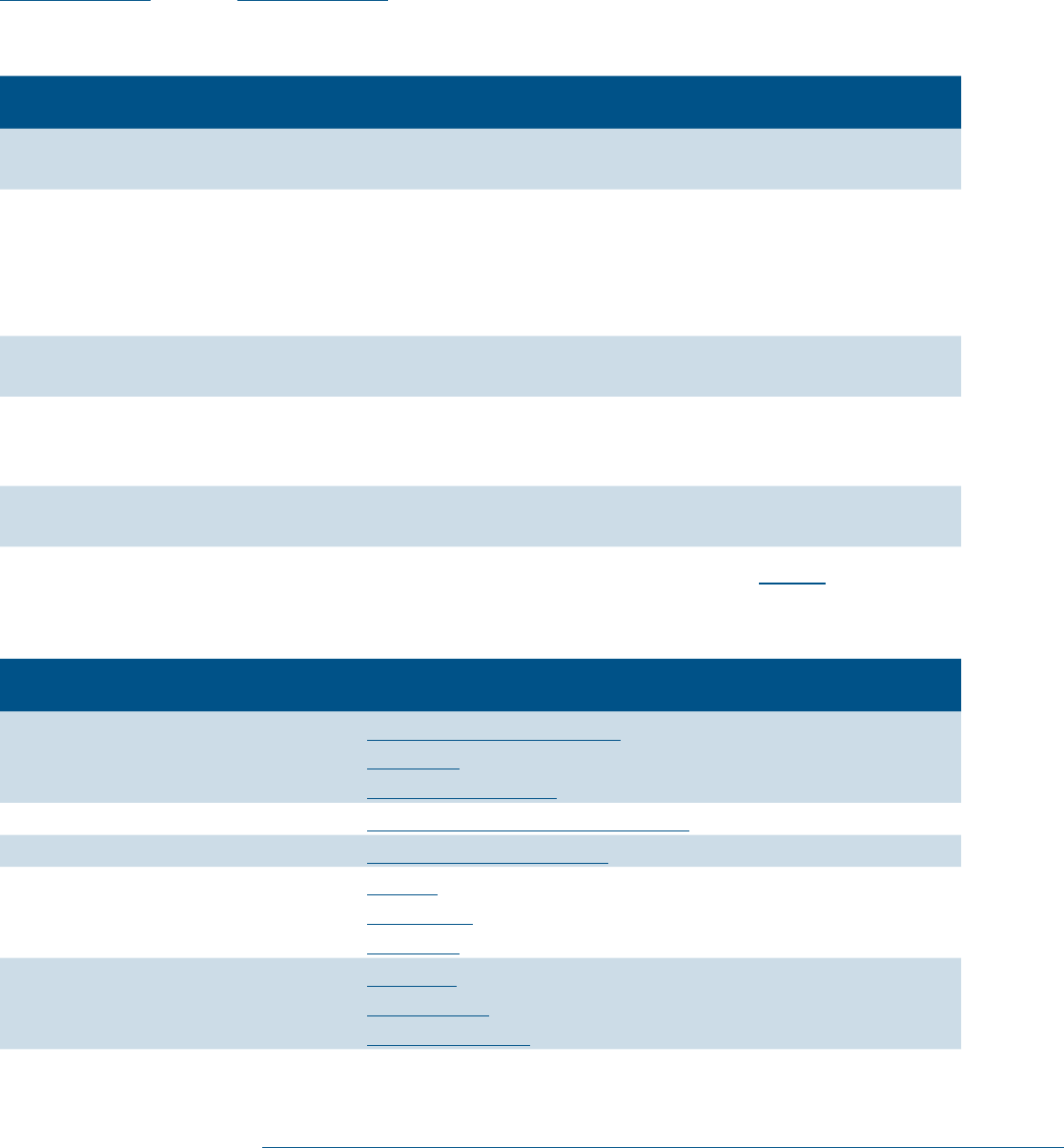

Document Guide: Cybersecurity Pracces

This volume provides small healthcare organizations with a series of cybersecurity practices to prevent,

react to, and recover from the ve cybersecurity threats identied below in Table 1 and discussed in the

Main Document. (See the Main Document for detailed denitions and descriptions of each threat.)

Table 1. Five Prevailing Cybersecurity Threats to Healthcare Organizations

Threat Potenal Impact of Aack

Social engineering Malware delivery or credential attacks. Both attacks further

compromise your organization.

Ransomware attack Information system assets locked and held for payment of ransom

(extortion). Disrupts normal healthcare operations. Prevents business

functions like electronic billing for treatment services. May result in a

breach of sensitive information and patient identity theft as well as the

permanent loss of patient records.

Loss or theft of

equipment or data

Breach of sensitive information. May lead to patient identity theft.

Insider, accidental or

malicious data loss

Removal of data from your organization (intentionally or

unintentionally). May lead to a breach of sensitive information as well

as patient identify theft.

Attacks against network

connected medical devices

Undermined patient safety, delay or disruption of treatment,

and well-being.

The cybersecurity practices and sub-practices to mitigate these threats are listed in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Cybersecurity Practices and Sub-Practices for Small Organizations

Cybersecurity Pracce Sub-Pracce for Small Organizaons

Email Protection Systems 1.S.A Email System Conguration

1.S.B Education

1.S.C Phishing Simulations

Endpoint Protection Systems

2.S.A Basic Endpoint Protection Controls

Access Management

3.S.A Basic Access Management

Data Protection and

Loss Prevention

4.S.A Policies

4.S.B Procedures

4.S.C Education

Asset Management

5.S.A Inventory

5.S.B Procurement

5.S.C Decommissioning

Document Guide: Cybersecurity Practices

8Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Pracce Sub-Pracce for Small Organizaons

Network Management 6.S.A Network Segmentation

6.S.B Physical Security and Guest Access

6.S.C Intrusion Prevention

Vulnerability Management

7.S.A Vulnerability Management

Incident Response

8.S.A Incident Response

8.S.B Information Sharing

Network Connected Medical

Device Security

9.S.A Medical Device Security

Cybersecurity Oversight

and Governance

10.S.A Policies

10.S.B Cybersecurity Risk Assessment and Management

10.S.C Security Awareness and Training

10.S.D Cyber Insurance

9Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Pracce #1:

Email Protecon Systems

Most small practices leverage outsourced third-party email

providers, rather than establishing a dedicated internal email

infrastructure. This section’s email protection practices are

presented in three parts:

• Email system conguration: the components and capabilities that

should be included within your email system.

• Education: how to increase staff understanding and awareness

to protect your organization against email-based cyber-attacks

such as phishing and ransomware.

• Phishing simulations: ways to provide staff with training on and

awareness of phishing emails.

Small healthcare organizations should avoid “free” or “consumer”

email systems. These email offerings may not have safeguards

in place that meet the requirements of the HIPAA Security

Rule to store, process, or transmit PHI. Most widely available

internet service providers offer a level of service that will apply

the appropriate safeguards that meet HIPAA Security Rule

requirements. Ensure all vendors sign a BAA to meet HIPAA Security Rule requirements.

Sub-Practices for Small Organizations

1.S.A: Email System Conguration

NIST Framework Ref: PR.DS-2, PR.IP-1, PR.AC-7

Consider the following controls to enhance the security posture of your email system. Check with your

email service provider to ensure these controls are in place and enabled.

• Secure email for business use. Organizations should ensure that basic spam/antivirus software

solutions are installed, active, and automatically updated wherever possible. Many spam lters can

be congured to recognize and block suspicious emails before they reach employee inboxes.

7

Additionally, organizations that want a defensive strategy against malware attacks may want to

consider deployment of a “sinkhole”. This utilizes a server designed to capture malicious trafc and

prevent control of infected computers by the criminals who infected them. A Domain Name System

(DNS) sinkhole can act as a major tool for eradicating the spreading of malware infection risk areas

and can be used to break the command and control connection. There are many excellent free open

source tools that can be evaluated to determine the best one for your organization.

7 “Update Your Software Now.” Federal Trade Commission. June 2019. https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/blog/2019/06/

update-your-software-now.

Areas of Impact

Sensitive Data, System Integrity

Sub-Practices

1.S.A Email System

Conguration

1.S.B Education

1.S.C Phishing Simulations

Key Threats Addressed

• Social engineering

• Ransomware attacks

• Insider, accidental or

malicious data loss

405(d) Resources

• Prescription Poster:

Email Protection Systems

• Five Threats Flyers:

¡ Social Engineering

¡ Ransomware Attacks

¡ Insider, Accidental, or

Intentional Data Loss

Cybersecurity Pracce #1: Email Protecon Systems

10Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

• Deploy multi-factor authentication (MFA) before enabling access to your email system. MFA can prevent

hackers who have obtained a legitimate user’s credentials from accessing your system.

8

Make sure

that MFA is in place for web access and your local client access. It’s popular to want to use IMAP or

POP3 settings protocols, but these might not support MFA and can leave a back door open to your

email mailboxes.

• Optimize security settings within your authorized internet browser(s), including blocking specic websites

or types of websites. Optimization of security settings can minimize the likelihood than an employee

will open a malicious website link. Most browsers assess the possibility that a site is malicious and

send warning messages to users attempting to access potentially dangerous sites. The University

of California at Santa Cruz has developed a guide for security settings on several widely used

internet browsers.

9

• Congure your email system to tag messages that are sent from outside of your organization as

“EXTERNAL”. Consider implementing a tag that advises the user to be cautious when opening such

emails, for example, “Stop. Read. Think. This is an External Email.”

10

• Implement an email encryption service or module. This enables users to securely send emails to

external recipients or to protect information that should only be seen by authorized individuals.

• Provide every employee with a unique user account tied to a unique email address. These accounts and

email addresses should not be shared. Have a process in place to terminate user accounts when the

employee leaves your organization.

1.S.B: Education

NIST Framework Ref: PR.AT-1

Implement education and awareness activities to assist your employees and partners in protecting your

organization against phishing attacks. Common phishing attacks include email messages that attempt to

trick you into:

• divulging your usernames and passwords.

• downloading and installing software (this is the primary mechanism of installing malware

or ransomware).

• procuring gift cards or conducting wire transfers (also known as Business Email Compromise (BEC)).

To educate your users, it is important to distribute awareness materials and train your employees and

partners. Establish and maintain a training program for your workforce that includes a section on phishing

8 “Back to Basics: Multi-Factor Authentication.” NIST Information Technology Laboratory/Applied Cybersecurity

Division. February 16, 2022. https://www.nist.gov/itl/applied-cybersecurity/tig/back-basics-multi-factor-

authentication.

9 “Web Browser Secure Settings.” University of California Santa Cruz Information Technology Services. September 25,

2020. https://its.ucsc.edu/software/release/browser-secure.html.

10 Smith, Andrew. “Cybersecurity for Small Business: Email Authentication.” Federal Trade Commission. February

8, 2019. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2019/02/cybersecurity-small-business-email-

authentication.

Cybersecurity Pracce #1: Email Protecon Systems

11Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

attacks.

11

All users in your organization should be able to recognize the phishing techniques outlined

below in Table 3.

12

Train your employees to do the following:

• Train your employees and partners to use the encryption module within your email system to minimize

the risk of information being intercepted by hackers.

• Train your employees to be careful when sending and receiving emails that contain personally

identiable information (PII) or PHI. When sending PII or PHI double check that the email address

of the intended recipient of the email message is correct so that the message is not received by the

wrong person.

13

• Train your employees how to report suspicious messages. These should be reported to the person

responsible for maintaining your IT system staff or contractor. That individual or service provider

can then advise the employee regarding disposition of the suspicious message. See Cybersecurity

Practice #8: Incident Response.

Table 3. Phishing Detection

Phishing Detecon Descripon

Check embedded links Validate that the URL of the link matches the text of the link itself. This

can be achieved by hovering (not clicking) your mouse cursor over the link

to view the URL of the website to be accessed. Always be careful when

clicking on an external link, as not all external links will direct you to a

trusted website.

Look for suspicious

“From:” addresses

Check received emails for spoofed or misspelled “From:” addresses.

For example, if your organization is “ACME” and you receive an email

from [email protected], do not open the email without verifying that it

is legitimate. You can check this by hovering over the sender’s name.

Legitimate addresses should match what is in the “From:” eld.

Be cautious with

“urgent” messages

If the email message requires immediate action, especially if it includes a

request to access your email or any other account, do not open the email or

take any action without verifying that it is legitimate.

Be cautious with “too

good to be true” messages

If you receive an unexpected message about winning money or gift

cards, do not open the email or take any action without verifying that it

is legitimate.

11 “Cybersecurity for Small Business: Phishing.” Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-

center/small-businesses/cybersecurity/phishing.

12 “How to Recognize and Avoid Phishing Scams.” Federal Trade Commission. May 2019. https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/

articles/how-recognize-and-avoid-phishing-scams.

13 “Security Tip ST04-014): Avoiding Social Engineering and Phishing Attacks.” Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security

Agency (CISA). August 25, 2020. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/avoiding-social-engineering-and-phishing-

attacks.

Cybersecurity Pracce #1: Email Protecon Systems

12Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

1.S.C: Phishing Simulations

NIST Framework Ref: PR.AT

An effective approach for training the workforce to detect a phishing attack is to conduct simulated

phishing and social engineering campaigns. The authorized cybersecurity personnel or third-party

provider crafts and sends phishing emails to users with email accounts. These emails have embedded

tracking components (e.g., to track link clicks). Tracking enables your organization to identify employees

who detect the email as a phishing attack and those who fail to detect the attack, opening the email or

clicking the emailed links. Your organization can then provide the appropriate training and feedback

as soon as possible after the event. Simulated phishing attacks provide a cause-and-effect training

opportunity and are incredibly effective. Consider conducting entire workforce phishing simulations on

at least a monthly basis. Develop specialized simulations for higher-risk areas within your organization.

These could be department-based (e.g., nance, human resources) or data-based e.g., highest-risk users).

Phishing and social engineering campaigns should track (and potentially reward) users that successfully

report the test message.

An effective phishing simulation should include:

• Implement regular (e.g., monthly, quarterly) campaigns with real-time training for your staff. Many

third-parties provide low cost, cloud-based phishing simulation tools to train and test your

workforce. These tools often include easy to distribute pre-congured training your workforce can

complete independently.

• Begin campaigns with easy-to-spot emails your workforce learns to recognize. Slowly increase the

sophistication of these simulations to improve the detection capability of your workforce. Also

consider sending email tests related to BEC, as discussed previously.

• Include targeted tests directed to leadership, accounts payable, payroll, and other workforce members

in positions that make them specic targets for phishing.

• Create special training and tests for workforce members who are frequently on the list of those who

clicked the link or opened an attachment.

CISA offers free phishing simulation services.

14

If you have budgetary limitations, it is advisable to contact

CISA and set up a service plan.

Although an anti-phishing campaign cannot stop the inbound ow of phishing emails, it will help your

organization identify any attacks that bypass established email security protections. Educated and aware

staff can become “human sensors” to inform you when a real phishing attack is occurring.

Key Mitigated Threats

1. Social engineering

2. Ransomware attack

3. Insider, accidental or malicious data loss

14 “Free Cybersecurity Services and Tools.” Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). https://www.cisa.gov/

free-cybersecurity-services-and-tools.

13Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

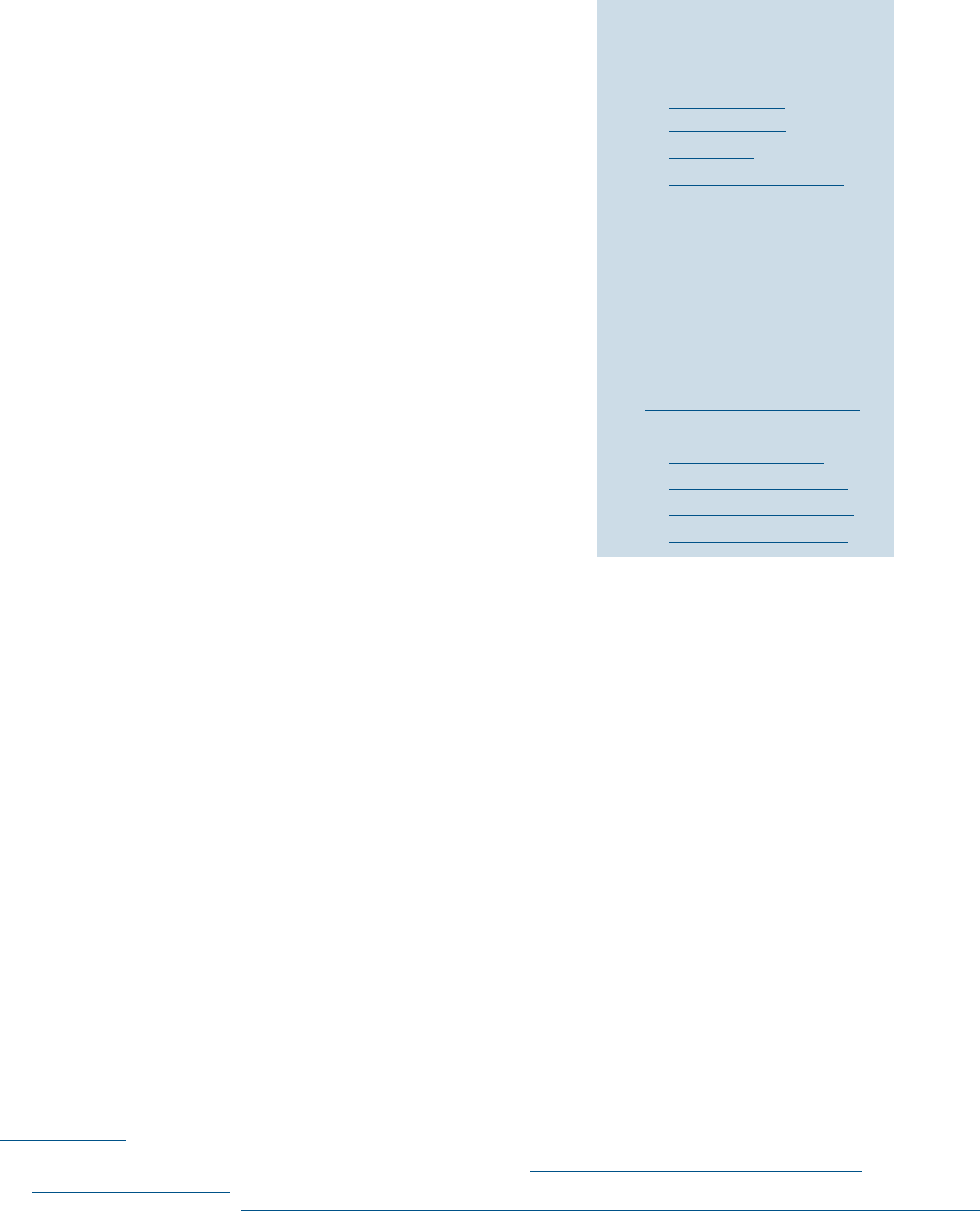

Cybersecurity Pracce #2:

Endpoint Protecon Systems

Endpoints are IT devices and equipment that can provide access

to your organization’s information network.

15

Endpoints on an

organization’s information network include desktops, laptops,

mobile devices, and other connected hardware devices (e.g.,

printers, medical equipment). Because technology is highly mobile,

computers are often connected to and disconnected from an

organization’s network.

Although attacks against endpoints tend to be delivered via email,

as described above in Cybersecurity Practice #1: Email Protection

Systems, they can also be delivered as client-side attacks. Client-

side attacks occur when vulnerabilities within the endpoint are

exploited. Recommended security controls to protect endpoints are presented below in Table 4.

Sub-Practices for Small Organizations

2.S.A: Basic Endpoint Protection Controls

NIST Framework Ref: PR.AT, PR.IP-1, PR.AC-4, PR.IP-12, PR.DS-1, PR.DS-2, PR.AC-3

Table 4. Effective Security Controls to Protect Organization Endpoints

Security Control Description

Manage administrative

accounts

Administrative accounts are created and used by those authorized to make

changes to the information system. A separate administrative account

should be created for each person authorized to have privileges as a system

administrator and used for the installation of software. Only authorized

personnel within an organization should be allowed to install software

applications. The administrator of the system should not conduct their

non-administrative business tasks using their administrative account,

rather their “regular user account.”

Remove unnecessary

administrative accounts

Most users in an organization do not need to be authorized as system

administrators with expanded system access and capabilities. Remove

administrative access on endpoints to mitigate the damage that can be

caused by an attacker who compromises that endpoint.

15 Pahl, Thomas B. “Stick With Security: Secure Remote Access to Your Network.” FTC Bureau of Consumer Protection.

September 1, 2017. https://www.ftc.gov/ news-events/blogs/business-blog/2017/09/stick-security-secure-remote-

access-your-network.

Areas of Impact

Passwords, PHI

Sub-Practices

2.S.A Basic Endpoint

Protection Controls

Key Threats Addressed

• Ransomware attacks

• Loss or theft of equipment

or data

405(d) Resources

• Prescription

Poster: Endpoint

Protection Systems

Cybersecurity Pracce #2: Endpoint Protecon Systems

14Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Security Control Description

Audit your software

applications

Audit software applications on each endpoint. Maintain a list of approved

software applications. Remove unauthorized software applications as soon

as they are detected.

Always keep your

endpoints patched

Patching (i.e., regularly updating) systems removes vulnerabilities that

can be exploited by attackers. Each patch modies a software application,

mitigating a threat that has been exposed. Congure endpoints to patch

automatically and ensure third-party applications are patched as soon as

possible. It is often necessary to reboot or restart applications or system

software after applying updates or patches.

Implement antivirus

software

Antivirus software is readily available. For example, Microsoft Windows 10

operating system software has antivirus and malware security protections

pre-installed for the end-user to activate. Other vendors offer free or low-

cost software applications that are effective at protecting endpoints from

computer viruses, malware, spam, and ransomware threats. Each endpoint

in your organization should be equipped with antivirus software that is

congured to update automatically.

Remove End of Life (EOL)

operating systems

Remove End of Life (EOL) operating systems, software, and applications.

Operating systems, software, and applications are considered EOL when

they are no longer supported by the vendor/provider and do not receive

product updates and security patches. Use of these products represents

a signicant risk to your data, information systems, and overall mission.

Operating systems, software, and applications that are no longer supported

by the vendor/provider should be removed from the environment.

Enable endpoint

encryption

Install encryption software on every endpoint that can connect to your

information systems, especially mobile devices such as laptops. Maintain

audit trails of this encryption in the event a device is ever lost or stolen.

This simple and inexpensive precaution may prevent a complicated and

expensive breach. For devices that cannot be encrypted or that are

managed by a third-party, implement physical security controls to minimize

theft or unauthorized removal. Examples include installation of anti-theft

cables, locks on rooms where the devices are located, and the use of badge

readers to monitor access to rooms where devices are located.

Enable network rewalls Firewalls create a “buffer zone” between your own network and external

networks (such as the internet). Most popular operating systems now

include a rewall, so it may be as simple as switching this on. Enable

rewalls for your endpoint devices. Firewalls are especially important for

mobile devices that may be connected to unsecured networks such as Wi-

Fi networks at coffee shops or hotels.

Cybersecurity Pracce #2: Endpoint Protecon Systems

15Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Security Control Description

Enable MFA for

remote access

For devices that are accessed remotely, leverage technologies that require

MFA before permitting users to access data or applications on the device.

Logins that use only a username and password are no longer considered

truly secure due credentials often compromised through phishing emails.

If your healthcare organization uses an EHR or accesses sensitive data through a software application

(either on the cloud or onsite), encrypt network access to these applications. Contracts with EHR vendors

should include language that requires PHI to be encrypted both at rest and during transmission to and

from your systems. Software applications that encrypt data prevent hackers from accessing sensitive

data, usually by requiring a “key” to encrypt and/or decrypt data.

For healthcare organizations that have IT resources or contract with vendors to manage their information

systems, audit the use of remote access software that is installed on endpoints to ensure they remain in

use. Check to make sure that MFA is enabled on software applications and operating systems.

Finally, educate your workforce members on the need to report the loss or theft of endpoints to the

appropriate team or designated manager inside your organization. For example, if a backpack with a

laptop is stolen, the employee should report the theft promptly.

Key Mitigated Threats

1. Ransomware attack

2. Loss or theft of equipment or data

3. Attacks against devices that affect patient safety

16Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Pracce #3:

Access Management

Healthcare organizations of all sizes need to clearly identify all

users and maintain audit trails that monitor each user’s access to

data, applications, systems, and endpoints. Just as you may use a

name badge to identify yourself in the physical work environment,

cybersecurity access management practices can also help ensure

users are properly identied in the digital environment.

Sub-Practices for Small Organizations

User accounts enable organizations to control and monitor each

user’s access to and activities on devices, EHRs, email, and other

third-party software systems. It is essential to protect user accounts

to mitigate the risk of cyber threats. Your IT specialist should

implement the security controls outlined below in Table 5 to manage

user access of data, applications, and devices.

3.S.A: Basic Access Management

NIST Framework Ref: PR.AT, PR.AC-1, PR.AC-6, PR.AC-4, PR.IP-11, PR.IP-1, PR.AC-7

Table 5. Security Controls Enabling Organizations to Manage User Access to Data

Security Control Description

Establish a unique

account for each user

Assign a separate user account to each user in your organization. Train and

regularly remind users they are not to share passwords. Through policy

and awareness training, have each user create an account password that

is different from the ones used for personal internet or email access (e.g.,

Gmail, Yahoo, Facebook).

Limit the use of shared

or generic accounts

The use of shared or generic accounts should be avoided. If shared

accounts are required, train and regularly remind users that they must sign

out upon completion of activity or whenever they leave the device, even for

a moment.

Sharing accounts exposes organizations to greater vulnerabilities. For

example, the complexity of updating passwords for multiple users on a

shared account may result in a compromised password remaining active

and allowing unauthorized access over an extended period.

Areas of Impact

Passwords

Sub-Practices

3.S.A Basic Access

Management

Key Threats Addressed

• Ransomware attacks

• Insider, accidental or

malicious data loss

• Loss or theft of equipment

or data

• Attacks against network

connected medical

devices that may affect

patient safety

405(d) Resources

• Prescription Poster:

Identity and

Access Management

Cybersecurity Pracce #3: Access Management

17Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Security Control Description

Tailor access to the

needs of each user

Tailor access for each user based on the user’s specic workplace

requirements. Most users require access to common systems, such as

email and le servers. Implementing tailored access is usually called

‘role-based access’.

Terminate user access as

soon as the user leaves

your organization

When an employee or contractor ends their relationship with your

organization, ensure that procedures are in place to terminate their

information system access immediately. Prompt user termination prevents

former workforce members or contractors from accessing patient data

and other sensitive information after they have left your organization. This

is particularly crucial for organizations using cloud-based systems where

access is based on credentials, rather than physical presence at a particular

computer or device.

Any shared or generic accounts in use should also be updated.

User job duties change Similarly, if a workforce member or contractor changes roles within your

organization, it is important to terminate access related to their former

position. Be sure to terminate account settings for the prior role before

enabling a new set of permissions based on the requirements for the

new position.

Provide role-based access New user accounts must be granted user-appropriate access to your

organization’s information systems, computer workstations, and programs.

Allow each user access only to the computers, devices, and programs

required to accomplish that user’s job or role in your organization. This

limits your organization’s exposure to unauthorized access, loss, and theft

of data if the user’s identity or access is compromised.

Establish separate accounts for administrator roles segregated from

regular user access where a workplace member has responsibility as a

system administrator in addition to their system access as a regular user.

Enable MFA for all accounts that are created for administrators.

Periodic review of access Be sure to conduct a periodic review of all employees’ access to your in-

formation systems on a predetermined time frame.

Congure systems and

endpoints with automatic

lock and log-off

Congure systems, applications, and endpoints to automatically lock and

log-off users after a predetermined period of inactivity.

Implement single sign-on Implement single sign-on systems that automatically manage access to

all software and tools once users have signed onto the network. These

systems allow your organization to centrally maintain and monitor access.

Cybersecurity Pracce #3: Access Management

18Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Security Control Description

Use multi-factor

authentication

Require multi-factor authentication to access areas of your network with

sensitive information. This requires additional steps beyond logging in with

a password—like a push notication to an app installed on a smartphone,

temporary code delivered through short message service (SMS), or a key

that’s inserted into a computer.

Implement MFA for

VPN Access

Implement MFA for VPN connections used to connect to your

organization’s network and systems (whether those systems are located

on-premise or in the cloud).

Restrict use of elevated

privileged accounts

System administrators should be issued two accounts—one with elevated

privileges and another for routine ofce functions. The former should be

reserved for essential operations and limited access to email and any social

media platforms. This elevated privilege account name should be treated

as sensitive information and should not be disclosed outside of your

organization’s IT department.

Disable inbound Remote

Desktop Protocol (RDP)

Disable inbound Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) on systems within your

organization’s network. Instead, set up a VPN tunnel for specic users and

systems that need to connect to your network remotely. Exploitation of

RDP is a common attack vector and considered a Bad Practice by CISA.

16

To monitor compliance with the practices listed in Table 5, implement access management procedures

to track and monitor user access to computers and programs. These procedures will promote consistent

provisioning and control of access throughout your organization. Examples of such standard operating

procedures can be found in the Cybersecurity Practices Assessments Toolkit.

Key Mitigated Threats

1. Ransomware attack

2. Insider, accidental or malicious data loss

3. Loss or theft of equipment or data

4. Attacks against network connected medical devices that may affect patient safety

16 “Bad Practices.” Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). https://www.cisa.gov/BadPractices.

19Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Pracce #4: Data

Protecon and Loss Prevenon

A data security breach is the compromise, loss, or disclosure of

sensitive data, including information relevant to your organization’s

business and PHI. Impacts to your organization can be profound

if data is corrupted, lost, or stolen. Data security breaches may

prevent users from completing work accurately or on time and could

result in potentially devastating consequences to patient safety, the

provision of care and their well-being. Good data protection and

loss prevention practices protects an organization and its patients.

Sub-Practices for Small Organizations

The compromise of sensitive data can be prevented several

ways. Data protection is based on understanding where data

resides, where it is accessed, and how it is shared. Throughout this

document, there are many tips to protect data and prevent loss. This section focuses on loss prevention

policies, procedures, and education.

4.S.A: Policies

NIST Framework Ref: ID.GV-1, ID.AM-5

• Set the expectation on how your workforce is expected to manage the sensitive data at their ngertips.

Most healthcare employees work with sensitive data daily, so it is easy to forget how important it is

to remain vigilant about data protection. Organizational policies should address all user interactions

with sensitive data and reinforce the consequences of lost or compromised data.

• Establish a data classication policy that categorizes data by its criticality and sensitivity. Examples of

data classication are Sensitive, Internal Use, or Public Use. An organization needs to identify the

types of data les and types of records relevant to each category. For example, the Sensitive data

category should include PHI, social security numbers (SSNs), credit card numbers, which may be

used to commit fraud, or may damage your organization’s reputation. Table 6 outlines and describes

possible data classications.

• Prohibit the use of unencrypted storage media and devices, such as thumb drives, mobile phones, or

including computer hard drives. Require encryption of storage media before use.

Areas of Impact

Passwords, PHI

Sub-Practices

4.S.A Policies

4.S.B Procedures

4.S.C Education

Key Threats Addressed

• Ransomware attacks

• Insider, accidental or

malicious data loss

• Loss or theft of equipment

or data

405(d) Resources

• Prescription Poster:

Data Protection and

Loss Prevention

Cybersecurity Pracce #4: Data Protecon and Loss Prevenon

20Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Table 6. Example Data Classication Structure

Classication Description

Highly Sensitive PHI that can be used for identity theft, nancial fraud, or damage the

patient’s reputation. Examples include SSNs, credit card numbers,

behavioral health information, substance abuse information, and other

patient treatment information.

Data access should be controlled to only those users who need it to

perform their job or patient treatment as well as requiring proper

authentication at login. This data must be managed in compliance with

applicable regulatory requirements.

Sensitive Clinical research data, insurance information, human resources/employee

data, and business nancial records.

Internal Data that should be protected from public distribution. Examples

include organization policies and procedures, contracts, business

plans, corporate strategy and business development plans, and internal

business communications.

Public All data deidentied in compliance with applicable standards information

that is publicly available or otherwise permitted to be disclosed by

applicable federal or state requirements.

4.S.B: Procedures

NIST Framework Ref: ID.GV-1, PR.AT-1, PR.DS-2, PR.DS-5, PR.DS-1, PR.IP-6, ID.GV-3

Procedures to manage PHI ensure consistency through clear and explicit instructions. Such procedures

should therefore be implemented alongside data access policies. The following methods may be used to

develop and implement data management procedures:

• Use the classications dened in your policies to establish data usage procedures. For example,

Highly Sensitive data might have additional restrictions around disclosure than Sensitive data.

Identify authorized users of PHI and other Sensitive data. Establish the conditions for how and when

this data may be accessed or disclosed.

• Train your workforce to comply with organizational procedures when sending PHI via email.

Prioritize end-to-end encryption of PHI when sent via email or other messaging platforms. Patients

can request and receive PHI via unencrypted electronic communications. HHS has developed

materials to help educate patients that unencrypted communications containing PHI could be

accessed by a third-party in transit.

17

• Use an application that employs recognized secure email protocol and network for transmitting

PHI and other sensitive data via email. Implement data loss prevention technologies to mitigate

the risk of unauthorized disclosure of PHI and other Sensitive data. Refer to Technical Volume 2,

17 “FAQ 570: Does HIPAA permit health care providers to use e-mail to discuss with their patients?” HHS Ofce for

Civil Rights. July 26, 2013. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/570/does-hipaa-permit-health-care-

providers-to-use-email-to-discuss-health-issues-with-patients/index.html.

Cybersecurity Pracce #4: Data Protecon and Loss Prevenon

21Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Practice #4: Data Protection and Prevention for details on the applicability of these

technologies to your organization.

• Train workforce members to avoid backing up data on storage devices that are not managed by your

organization or a user’s personal cloud service. For example, do not allow staff and physicians to

congure any workplace mobile device to back up to a personal computer unless that computer has

been congured to comply with your organization’s encryption and data security standards.

Note: Leveraging the cloud for backup purposes is acceptable if there are service and business

associate agreements in place with the vendor. Ensure compliance with agreements through

verifying the security of the vendor’s systems. Data being backed-up should be encrypted prior to

storage to a cloud vendor’s system.

• Apply appropriate safeguards to protect archived PHI to prevent unauthorized use or disclosure.

Audit and monitor access to this data to detect unauthorized use or disclosure.

• Ensure obsolete data are removed or destroyed properly once the retention period has elapsed.

Just as paper medical and nancial records must be fully destroyed by shredding or burning, digital

data must be properly disposed of to ensure that they cannot be inappropriately recovered. Discuss

options for properly disposing of outdated or unneeded data with your IT support. Do not assume

that deleting or erasing les means that the data are destroyed. See the Cybersecurity Practices

Assessments Toolkit for a sample data destruction form that can be used to ensure that data are

disposed of appropriately.

• Retain and maintain only data your organization requires to complete work or comply with records

storage requirements. Minimize your organization’s risk by regularly removing unnecessary data in

all your applications (as well as le folders of documents, spreadsheets, images, pdfs, etc.).

4.S.C: Education

NIST Framework Ref: PR.AT

Communicate the policies and procedures you implement to your staff. Make sure that all staff members

know how to classify and protect data as well as understand how the risks of data loss can affect

your organization.

• Provide educational and awareness materials to staff and physicians about organizational policies

implemented to safeguard information systems and data. At a minimum, provide annual and periodic

refresher training on the most salient policy considerations (e.g., the use of encryption and safe

transmission of PHI).

• Maintain a record of workforce training sessions, topics presented, and attendance.

Key Mitigated Threats

1. Ransomware attack

2. Loss or theft of equipment or data

3. Insider, accidental or malicious data loss

22Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

Cybersecurity Pracce #5:

Asset Management

Organizations manage IT assets using processes referred to

collectively as IT asset management (ITAM). ITAM is critical to ensure

appropriate cyber hygiene controls are maintained across all assets

in your organization.

ITAM processes should be implemented for all endpoints, servers,

networking equipment, and cloud applications. ITAM processes

enable organizations to understand their devices, and the best

options to secure them. The practices described in this section may

be used to support many of the practices described in other sections

of this volume. Although it can be difcult to implement and sustain

ITAM processes, such processes should be part of daily IT operations

and encompass the lifecycle of each IT asset, including procurement,

deployment, maintenance, and decommissioning (i.e., replacement

or disposal) of the device.

Sub-Practices for Small Organizations

5.S.A: Inventory

NIST Framework Ref: ID.AM-1

A complete and accurate ITAM leveraged by your organization facilitates the implementation of optimal

security controls. This inventory can be conducted and maintained using a well-designed spreadsheet.

The following information should be captured for each device:

• Asset ID (primary key)

• Host Name

• Purchase Order

• Operating System

• Media Access Control (MAC) Address

• IP Address

• Deployed To (User)

• User Last Logged On

• Purchase Date

• Cost

• Physical Location

Remember to include all devices owned and leveraged by your organization. This should include

workstations, laptops, servers, portable drives, mobile devices, tablets, printers, medical devices,

Areas of Impact

PHI

Sub-Practices

5.S.A Inventory

5.S.B Procurement

5.S.C Decommissioning

Key Threats Addressed

• Social engineering

• Insider, accidental or

malicious data loss

• Loss or theft of equipment

or data

• Attacks against network

connected medical

devices that may affect

patient safety

405(d) Resources

• Prescription Poster:

IT Asset Management

Cybersecurity Pracce #5: Asset Management

23Technical Volume 1: Cybersecurity Practices for Small Healthcare Organizations |

routers, access points, rewalls, software applications, and smart phones. Refer to Technical Volume 2,

Cybersecurity Practice #5: IT Asset Management for more information on how to construct and maintain

an effective inventory of IT assets.

5.S.B: Procurement

NIST Framework Ref: ID.AM-6

Upon creating the ITAM system, it is important to record each new IT asset as it is acquired. This requires

establishing standard operating procedures for procurement. Generally, it is advisable to assign the

responsibility of collecting information on new assets to the purchaser within your organization.

As an asset is acquired, it is critical to tag it with an asset tag. These tags can be physical or logical. The

tagging process ensures that the asset has a unique ID that can be used to identify it in the ITAM system.

Using existing data (e.g., hostname, IP address, MAC address) as the unique ID is not recommended,

because these elds may change, potentially creating duplicate records.

5.S.C: Decommissioning

NIST Framework Ref: PR.IP-6, PR.DS-3

IT assets no longer in use should be decommissioned in accordance with your organization’s procedures.

Small organizations should consider working with an outside service provider specializing in secure

destruction of IT hardware assets and data stored on media. Such providers can ensure that all data,